There are few threshold-crossing moments more dramatic than the one in Shadow of the Colossus, the intro is just pure untouched nature. There are rocky cliffs and deep forests and pouring rain and they all kind of smother our protagonist. Apart from him, there’s really nothing man-made to be seen. And then there’s suddenly something. There’s a building on the horizon, an enigmatic shrine that could be fifty years old or a thousand. And then we step through it.

Level design in games sometimes feels at odds with the majestic art of the world surrounding it. For example, this vista in Dark Souls 3

Look at how sprawling the city is, how beautiful and ornate it appears. This is the closest to that city we’ll ever get. As I wondered through the handful of alleys I was allowed in, the Ringed City felt less like a city, and more like a projection. It felt like it kept reminding me that this world only exists for me and it’s made only to be conquered. But Ueda defies this convention. Ico and The Last Guardian take place in fantastical worlds, but they are worlds you’re forced to reckon with.

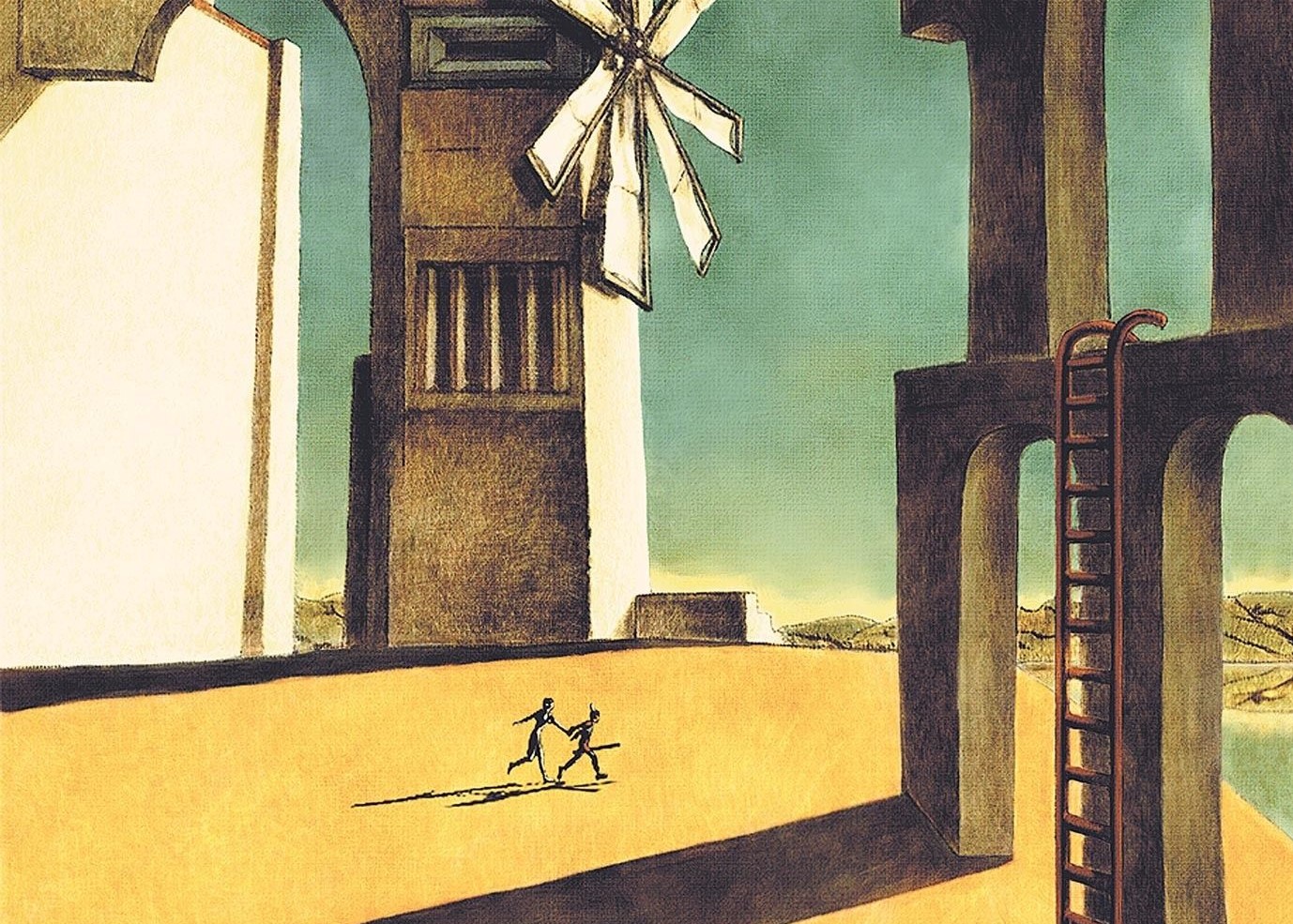

Ico takes place entirely within a massive castle, and there is no single part of this castle you don’t explore. Every courtyard, every island, every parapet, you even traverse its horrible mechanized underbelly only to ultimately loop back around to where you were first dropped off. I remember when I first played Ico, I was amazed when I would look down and see places that I had already been far below me in the world. Playing it now, I realized that’s true of every space in the game. Nothing is spurious, everything is really there.

And honestly, the brilliance of Ico just seems like a warmup when compared to The Last Guardian. The level of interconnected design here is staggering. Some of the structures reach higher than you can even crane your neck towards, and yet every part of each of them play some vital role in your quest to escape. I can’t get over the scene where you’ve just spent ages climbing this tower, up and up and up, and then it falls and it takes you across basically the entire map.

And yet these worlds are carefully paced to not feel like a checklist of places to traverse. Every piece of exploration is necessitated by realistic feeling obstacles. There aren’t arbitrary “collect 10 lizards and then you can pass” barriers, they let you get tantalizingly close to your goals before smashing you down to earth. Your relationship with the environment is frequently antagonistic but it never feels forced. There is no projection in Ueda’s work, I left both Ico and The Last Guardian knowing that my blood, sweat and tears littered every inch of their ruined worlds.